Tales from the Fairy Farm

Could this be the location for The Fairy Podcast's very first field report? Fiona has mentioned she'd be willing to spend the night camping on a fairy fort at Pat Noone's farm in Galway, Ireland. While I admire her bravery, it's quite possible that the night could end up somewhere between 'Don't Be Afraid Of The Dark' and 'The Blair Witch Project'. However, while Fiona explores the underworld for seven years I'll loyally continue the podcast on my own until she returns to the world above.

'Looking at fairies on my farm is the same as looking at traffic in Dublin' - Farmer who has 'the words' celebrates May Day

“Looking at fairies on my farm is the same as looking at traffic in Dublin. But they don’t come everyday.”

“I kind of expect it. When I was younger if I hadn’t seen them, you’d think there was something wrong. I’ve seen them on a good few occasions after that.”

Pat Noone (52) lives on a 60-acre farm in Galway, and says that 16 acres of it is a fairy field – complete with a fairy fort, a fairy tree and a tunnel running through it.

On his land also lies a megalithic cairn and a fairy stone, monuments that have attracted visitors as far away from Pakistan.

“[The fairy field] has the portal to the fairies – where the whitethorn meets the blackthorn. I have a cairn where an Irish chieftain was buried - there are a lot of those in Sligo.”

“[The fairy field is] a very special place and people have come out frightened out of it.”

Growing up, Pat would hear his father regal visitors with folklore tales, and he’d see him giving tours around the farm.

“My father was a historian as well as a great folklorist, and had a lot of history of the local area – he was an authority on local history.”

“When I was small, people would bring him a half quarter of tobacco and he’d bring them around and show them the fairy forts and the fields.”

“I was never frightened of the fairies, I’d heard a lot of stories about them. I’ve been farming since I was 14 or 15 and I ran into the fairies because I was up all night calving or lambing.”

“I met them on a few occasions, I chatted to them. They say you should never take a drink from the fairies, but I took a drink from them.”

Today, May 1, is one calendar day in particular that Pat keeps watch for fairies – and hares.

“I’ve often seen the Irish hare disappear into the hills in the morning, they become fairies early in the morning.”

Traditionally on May 1, a 'May Bush' which is usually a Whitethorn (Fairy Tree), is decorated with rags and colourful ribbons to pay homage to the fairy folk and make wishes for the year ahead.

May Flowers are also traditionally thrown onto roofs of houses on May 1 to appease the fairies.

“Every farmer is up May morning because he doesn’t want another fairy to steal his luck. That’s a big fairy morning; it’s the big day that the fairy has real power... and they have given real power to other people on May day.”

“When the fairies will give you the words, that’s when the magic comes in. I got them from my father, he got them from the fairies. He was sick for a year twenty years ago, and he had the opportunity to give them to me before he died.”

“I’ve seen a few people coming to me looking for the words, but I won’t because it can be abused as well.”

Possessing the sacrostanct "words" gives a person a healing power, Pat believes, and also the power for a little witchery.

He explains: “If you put eggs on another property on May morning you can steal his luck, but you have to have the words, that is crucial.”

“I can make fairy water as well, I have a big stone on the field, and because I have the words, it can heal the land and people.”

What about other supernatural forms, like the banshee? Is she someone he'll happily greet?

“I’ve seen her on a few occasions, it was scary enough, I didn’t speak to the banshee at all, I kept going on my way. She was combing her hair, a young woman, it was in spring time, this time of the year, and she was sitting on the stone on a few occasions. I didn’t speak to her. Everyone has something that they’re afraid of and that was mine. But nothing ever happened to me.”

“I haven’t had any bad experience because of it, but it stuck in my head about death, and that’s why I didn’t speak to her.”

Farming the land from a young age, Pat says, gave him an easy opportunity to meet the fairies.

“I was about 17 or 18, I’d be out minding cows, I was always out fishing and hunting at night. It was all-night work, and I like outdoor sports. So I wasn’t in the kitchen [growing up], I was reared outdoors.”

“I was coming down after looking at the cows in that 16-acre field. I heard the music and saw the fairies dancing and I went over and got talking to them. They talked English to me, I had no problem talking to them. They told me they just wanted me to keep the land the way it was, and told me not to take any of the bushes out. I listened to the music and I went home.”

“I have great luck with the stock, with farming, you’ll have your ups and downs with sick animals and nature takes its course, but overall I’ve had very good luck with the farm. And I don’t use any chemicals or sprays. That’s what the fairies told me. I use no weed killers at all whatsoever. It’s not the modern farm that people expect, I let the ditches grow naturally and then trim them back with the saw. It’s left naturally here.”

Storyteller Steve Lally, who recently wrote a book 'Irish Gothic, Fairy Stories from the 32 counties of Ireland' with his wife Paula, says folklore is still very much a living part of contemporary Ireland.

"Even when people say they don't believe they still wouldn't dream of cutting down a fairy tree. Myself and Paula have heard stories from people who live in cities and towns who heard the wail of the Banshee. In ancient times boys were put in dresses as baby's to protect them from being stolen by the fairies, because boys were more sought after than girls in the fairy world."

"This ritual for example still exists today where we see both boys and girls dressed in christening gowns."

The day Sweden’s trolls and fairies wept...

This curious tale by Victoria Martinez highlights what could be the downside of being an ambassador for the wee folk. Fairy folklore is generally perpetuated via the arts, be it through literature, film or painting, those who dedicate their lives to spreading the word of the fae feel some form of personal benefit that could be perceived as a reward bestowed by the little people. But what happens when you no longer want to fly the flag for the fairies and move on to pastures new? Do you think you'll just be able to walk away and leave it all behind or do you think those who you've spent years working for will want some form of recompense? Once you've eaten fairy fruit it would appear that you belong to them and any attempt to get away will be marred.

So this following story serves as a warning to those, such as myself, who artistically dabble in fairy folklore. Leaving might not be that easy or advisable, especially if you plan on making your escape by train or boat...

On November 20th, 1918, a tragic ferry accident claimed the life of a Swedish artist whose enchanting depictions of folk and fairytale creatures still capture the imagination.

In the seemingly infinite forests of the Swedish province of Småland, artist John Bauer lived for much of his life among the gnomes, trolls, fairies, fair maidens and gallant princes he brought to life in his art. As a child, his summers were spent exploring the forests around his family's summer villa near Lake Rocksjön in Jönköping. After a period of European travel, he and his wife Esther, also an artist, settled down in a similar location not far away at Lake Bunn near Gränna.

"He was inspired by the areas around Södra Vätterbygden and used to always return to these places. It was here that he captured the environment [for] his ‘Bauer forests’, which he populated with fairy tale-like creatures like trolls and giants, knights and princesses", according to the Jönköping County Museum.

His reputation as an artist was founded on the countless captivating illustrations he created of these mythical creatures during the early 1900s for the Swedish folk and fairy tale annual Bland tomtar och troll (Among Gnomes and Trolls). Between 1907 and 1915, Bauer’s art captured the spirit of Nordic mysticism and "reflected… a world where the physical reality and the mythical are present at the same time", according to Sweden’s National Encyclopedia.

However great his love of the forest, by 1918, life there was far from a fairy tale. After the couple’s son was born in 1915, Esther had put her own art career on hold, and became increasingly unhappy with life in Bauer’s enchanted but isolated forest. Bauer himself was often away, pursuing new genres of art. The couple’s marriage was in danger. The solution was to move to a new home in Stockholm.

It is said that a horrific train accident near Norrköping in October 1918, which claimed 42 lives, persuaded the family that it would be safer to make the journey from Gränna, near Jonköping, to Stockholm by boat. So, on November 19th, 1918, the couple and their three-year-old son boarded the steam ferry Per Brahe.

In addition to the 24 passengers and crew members, the small ferry was so overloaded with cargo, including Husqvarna stoves and sewing machines bound for sale in Stockholm, that much of it had been placed on deck.

The dangerously unstable boat stood little chance against the storm that hit within hours of its departure. In sight of the port at Hästholmen, located some 33 kilometers upland from Gränna, the Per Brahe capsized in Sweden’s Lake Vättern during the early hours of November 20th. Everyone on board perished.

Today, the site of Bauer’s childhood summer villa in Jonköping is the John Bauer Park, and the 46 kilometre John Bauer Trail between Gränna and Huskvarna passes through Bunn, where the Bauer’s lived before their tragic deaths in 1918. In these locations, as well as in the Jönköping County Museum, which holds the world’s largest collection of John Bauer’s art, it is still possible to discover both the real and imagined worlds he inhabited more than a century ago.

The Right and Wrong of Fictional Fairies

For me, the list of things that people get wrong about fairies is vast, but the one thing that tops it is fairy doors. I fucking hate fairy doors. For those of you who are pro fairy door, remind yourselves of the country code, ‘Take nothing but photographs and leave nothing but footprints’. This does not include ‘and also nail a plywood door covering in pink glitter and tinsel to a tree and possibly add a small doormat with a quirky quote’. It’s a new form of acceptable vandalism that not only spoils the sanctity of nature but it also promotes a candy covered facade to ancient fairy folklore for the new wave of tutu wearing unicorn lovers. If you remind yourselves of days gone by when fairies were considered (and still are in many places) lustful, nasty and cruel creatures as likely to kill you as lead you out of the forest. Even the benevolent fairies could be capricious and vindictive if wronged or disprespected in some way. A fine example of pissing off the children of the forest would be to nail a shit pink glittery door to a tree in a patch of ancient woodland. Am I the only one who can see the correlation between the popularity in fairy doors and the increase of people who go missing in forests and woodland? Here’s an avenue of investigation David Paulides hasn’t explored yet for sure!

Anyway, rant over.

This interesting article from Agora, the Pathoes Pagan Channel discusses elements of fairy folklore that some writers get horribly wrong. While I don’t agree with all of it, it goes some way to get people back on the right path through the woods…

Irish-American Witchcraft: The Right and Wrong of Fictional Fairies

This is a question that I was asked to look at on social media and I thought here was probably the best venue. Fairies are a hot topic in fantasy and urban fantasy and have been for decades, so what are novels getting right and where are they going wrong? It’s a good question and also an important one I think as I see more and more pagans adopting beliefs from fiction rather than folklore.

In and of itself its fine to have beliefs from odd sources – entire religions are founded on fiction and there’s nothing wrong with deciding to go with a belief you gleaned from a novel – it only becomes a problem when its put forward as genuinely older folk belief and becomes mainstream. Because when that happens, when it becomes popular under the guise of genuine traditional folklore, it actively erases the older cultural folklore which in many places is already struggling.

When a dominant culture starts to rewrite minority folklore not from a place of belief but for entertainment, even if those rewritten ideas are then absorbed again as beliefs, it’s a big problem. Not only because it accelerates the decline of the original culture but also because it raises the question of how much depth these new beliefs actually have to them.

Where Fiction Gets it Right

Fiction does get fairy folklore right, although some books are definitely closer to the mark than others. What follows will of course be generalizations based on a variety of different books and series, so even though I’m saying fiction gets these details right there will always be examples of books that get these bits wrong as well. Such is the risk with a diverse market.

Iron – most books I’ve seen do correctly make iron a substance fairies avoid or are harmed by. Different authors handle this a variety of ways because folklore is vague on the how and why of iron’s apotropaic qualities. It is widespread and well known and something that is found in many books in a way that is either true to folklore or fairly close.

‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ – although it’s often played as a trope, and sometimes terribly mauled especially in young adult novels, many authors do follow the Scottish folklore of there being two groups of fairies, one of which is more positively inclined towards humans the other being more malevolent. While this isn’t a universal concept it is from Scottish folklore specifically and has gained wider popularity.

Human-sized Fairies – a bit more hit or miss but increasingly more common in books to see fairies being depicted in a range of human sizes rather than as tiny. In folklore its clear that fairies appeared in many different forms and could be tall or short. While we do see some very tiny fairies those are actually rare in folklore and very specific in location and backstory. Most fairies are described as being between 4 and 6 feet tall, occasionally a bit shorter or taller.

Variety – Fiction is usually pretty good about breaking out of the idea that fairies are all tiny winged sprite-like beings and instead including a selection of different beings. This is true to folklore, where the word fairy is a generic term for an Otherworldly being. Also fiction recently seems to be doing well using synonymous terms like fae along with various spellings of fairy, all of which are inline with folklore (fun fact there’s something like 90 different recorded spellings for the word ‘fairy’ in writing since the term first appeared.)

Time Shift Between Worlds – The fiction I’ve read does a good job of staying true to the idea that there is a time shift between our world and Fairy, which is very accurate to folklore.

Where Fiction Gets It Wrong

While there are a few points of actual folklore that make it into books there’s also a wide array of misinformation and plain nonsense that shows up as well usually not intended to be framed as folklore at all but simply the author’s storytelling and imagination at play. Honestly this is the bulk of most mainstream popular fairy books (and rpgs). Plotlines take precedence over folklore and the result is a good story that is disconnected from any actual folklore. I could easily have a dozen items on this list but I’ll stick to the most common ones I see that are both side spread and crossing over into pagan spiritual belief.

Multiple Named Courts – In Scottish folklore there are two courts of Fairy, the Seelie and the Unseelie; in other folklore there aren’t named courts at all. But its become popular in fiction over the last 20 years or so to expand the Scottish system, first including a third ‘wyld’ court then going further. One series has 7, while a popular RPG has more than a dozen. This is something I know for a fact is finding its way into paganism because I am often asked about it and run across people referring to ‘courts’ I recognize from specific books or games.

Whose In Charge? – Modern fiction has not only created new named courts but has also given new Queens to the existing Seelie and Unseelie courts of Scottish lore. These range depending on the story but Shakespeare’s fairy queens, Mab and Titania, often put in appearances. This is also highly problematic from the perspective of actual folklore where the Queen of the Unseelie court is usually understood to be Nicnevin and the Seelie queen is never named; putting English fairy Queens on Scottish fairy thrones is a lot of politics that are painful to even consider and speak of authors choosing names out of convenience rather than doing research. Some books choose random deities to head a known fairy court – usually the traditional Seelie and Unseelie – while in other cases entirely new beings have been invented.

Unseelie Emo Love Interests – Super popular trope in young adult urban fantasy and also edging into adult genres. The idea that the Unseelie aka the ‘Bad’ fairies, are actually the good guys and just need the right person to show them their good guy potential/save them/motivate them/whatever. Cue My Chemical Romance playlist here. The reality is that while the Unseelie are certainly more nuanced than straight up evil they certainly aren’t a bunch of eternal teenage boys looking for the love of a good misfit.

Important Humans – This one makes complete sense in a novel, because obviously in most stories the main character (MC) is going to be human and therefore obviously special and significant and get into magical adventures. So we see lots of stories where the human MC is absolutely pivotal to the local fairies, meets the Queen, marries the prince, saves the world, etc., The reality in folklore is that when fairies take an interest in humans its always for a reason and that reason is always to the fairies’ advantage. In some cases they would connect to human witches and teach them, true, but the witch always had reciprocal obligations. In most stories the human ended up as a servant, entertainment, or breeding stock. Basically in folklore (and reality) humans aren’t the center of very much.

Over Anthropomorphizing – Not physically but emotionally and mentally. In folklore it’s clear that fairies are very alien in their motivation and actions to human beings yet in fiction they often act pretty much like humans. This lends itself to an increasing idea that fairies are kinder and nicer than they often appear in folklore and also changes the way people approach interacting with them. In folklore they often seem cruel and it may not be that they are but that we are unable to understand their motivations most of the time. Like mice trying to understand house cats.

Final Thoughts

I do think there are examples of good fiction that includes fairies which are truer to folklore. I’ve written previously about some of my personal favorites in a blog titled ‘Good Fairy Fiction‘ and people added more suggestions in the comments on that one. I would still however note that the best fairy fiction must always make some slight concessions for plot and characterization so that nothing is ever aligned completely with folklore; what we want in a good story and what we get in fairy anecdotes don’t mesh perfectly.

People often question why any of this matters, why we should care whether a belief is genuinely folkloric or pulled from modern fiction or invention. There is of course a fluidity to folklore that means today’s urban legend is tomorrow’s folk belief and sometimes today’s fiction becomes the folk belief of the next century. This is a particularly touchy question in modern paganism where people are often looking for any and all sources on a subject like fairies. But I think Nimue Brown sums it well in a recent blog, saying that there is a difference between being part of a culture and its evolution and being outside of it and taking material from it to use outside its context. Too often what’s being taken as belief from modern fiction is the latter, material that is disconnected from actual cultural belief and born simply as a plot device.

If you are seeking to incorporate belief in fairies into your spirituality, to approach belief in them the way the modern living cultures that believe in them do, I suggest treating them as you would a foreign human culture you are interested in learning about. And I would sincerely hope, to forward that analogy, if you want to learn about Ireland you would look to solid non-fiction sources and accounts written by people with first hand experience, rather than fiction. In the same way with fairies while fiction can be fun and entertaining we need to be careful not to blur that line and start seeing it as depicting actual folklore, because most of the time it isn’t.

Exeter University Students to Summons Demons and Fairies in New Study

This article taken from The Devon News has all the hallmarks of a classic H.P. Lovecraft or Arthur Machen story. A group of University history students conduct a study into ancient magick and attempt to summon fairies and demons using rituals from 16th century manuscripts; what could possibly go wrong? Could this be the folklore equivalent of the Cern project? The opening of portals to the underworld and the awakening of ancient gods? I certainly hope so!

Exeter University to study best way to summon fairies and demons

Researchers will start with ancient spell books up to 600 years old

The mysterious methods used by people in bygone times to summon fairies to help navigate the trials and tribulations of day-to-day life are set to be uncovered.

Researchers from the University of Exeter have launched a new study to examine collections of 15th to 17th-century spell books and grimoires that gave instructions on how to summon and conjure fairies, demons and other spirits.

This period, starting in the late medieval times, saw the writing of many books giving instructions on how to perform sorcery and necromancy, and fairies played an important role.

Among the common theories were that they were demoted angels, spirits of the dead, prehistoric human precursors, and minor deities in pagan beliefs.

Fairies were not always considered as virtuous, particularly as Puritanism grew after the Reformation in the 16th century.

A popular phenomenon was the will-o'-the-wisp, a fairy that led travellers astray at night.

As such, various spell books were written to conjure fairies, demons and other spirits for noble and nefarious purposes.

Samuel Gillis Hogan will begin trawling through ancient manuscripts in many of England's libraries to find evidence and records of how people thought they could harness the power of fairies over the 300-year period, and what influence this had on people's lives and culture.

"Fairies were thought of as wondrous and beautiful, but mostly dangerous," he said.

"But people wanted to summon them and harness that power for their own gain. For example, fairies were often asked to teach how to heal people."

Mr Gillis Hogan, who is starting a PhD, will move from Canada to join a team of historians at the University of Exeter who are already investigating the history of magic.

"The study of the history of magic is a rich vein for analysis and insight into the history of thought, religion, medicine, science, and philosophy," he said.

"It shows much about beliefs at the time. By fully understanding these practices, we can often reconstruct how it was perfectly rational given contemporary beliefs.

"It's easy to look down our noses at past or present cultures and dismiss them as 'backwards' or 'primitive', but intimately understanding these very different worldviews emphasises that our own is simply one among many."

Mr Gillis Hogan will be supervised by two historians, Professors Catherine Rider and Jonathan Barry.

His PhD will be funded by a Rothermere fellowship which supports students who have previously studied at the Memorial University of Newfoundland to study in the UK.

Anatomical Study of the Common Fairy

From the private collection of Octavius Rookwood (August 16, 1853 – July 17, 1936), American British pharmaceutical entrepreneur, explorer and occult researcher.

This specimen was acquired by Rookwood during a stay with the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire at their home, Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, UK. A farmer from the village of Allestree, situated approximately 30 miles to the south of the Chatsworth estate, discovered the small fairy body when his faithful rat catcher left the limp remains on his kitchen floor. The cat normally left daily 'glory gifts' for the farmer which comprised of mice, rats and small birds but during the spring of 1902 it started to leave dead fairies. Rumours spread throughout the local villages and the farmer began to exhibit them at the pubs and cattle shows for a small fee. Rookwood got wind of the story and promised the farmer a handsome reward if he could supply him with a fresh specimen. The farmer promptly delivered two fairy corpses to Rookwood; one complete and another partially devoured by the farm cat.

The framed specimens were exhibited at the Royal Anthropological Institute in London for a number of years before disappearing in 1911. They were rediscovered in 1998 during the restoration of Rookwood's ancestral home by the National Trust. Dismissed as a late Victorian sideshow oddity, the fairies were auctioned at Sotheby's to raise funds for the upkeep of the estate and purchased by a private collector believed to be a prominent Canadian businessman.

The Fairy Census: 2014 – 2017 is out

British and Irish fairies have been around since 500 AD. Ever since the Cottingley Fairy Hoax (1917-21) they have been in decline, however. In the footsteps of The Lord of the Rings and The Game of Thrones, British fairies are regaining their old lustre. Did you know that many British fairies don’t have wings and can be the size of a leaf or up to 15 foot tall?

The Fairy Census is an attempt to gather, scientifically, the details of as many fairy sightings from the last century as possible and to measure, in an associated survey, contemporary attitudes to fairies. The census was inspired by an earlier fairy census carried out by Marjorie Johnson and Alasdair Alpin MacGregor in 1955/1956, a census that was published in 2014.

Simon Young has offered a copy of this incredible survey for FREE!

Do download your copy now.

If you wish to submit your own sighting for the next census there are two (anonymous) census forms: one for witness accounts and one for second-hand accounts (experiences of grandma, uncle, friend etc). Confidentiality is assured and, in the case of publication, personal details will be changed to assure anonymity. Note, however, that by filling out these forms you approve their use in an academic survey.

1) If you witnessed the event first-hand click here

2) If you are describing an event experienced by someone else click here

There is also a general survey on individual beliefs about fairies, using an innovative visualisation technique. Here no experience or witness account is necessary: anyone can fill out the survey who understands the word ‘fairy’. Adults are welcome to lead children through the questions, even children as young as three or four.

3) If you want to do the survey on fairy belief more generally click here.

Paranormal News Insider Radio Discusses Pixie Bones

A week on and the story of the Pixie skeleton is still doing the rounds in the US. This week it was covered by The Paranormal Insider Radio Show which is hosted by Dr. Brian D. Parsons who has a wide background in paranormal investigation, UFOlogy, and cryptozoology, is an author of six books and is a public speaker on a variety of topics.

Dr Parsons contacted me prior to the show to ask if I had further information on the Pixie. I pointed him towards my last blog post and until the German facility releases more information we're kind of all left in the dark. Personally, I'm under the impression we will never hear from them again and the bones now reside boxed up in some huge warehouse alongside the Ark of the Covenant and a myriad of other artifacts that the government don't want us to know the truth about.

The Pixies is discussed from 18:00.

You can also listen to episode 7 of The Mystic Menagerie Podcast where Freddie Valentine and I talk about the Pixie bones for the very first time (starts 17:00)

Pixie Skeleton Mystery Reappears in the US

Almost 2 years after The Mystic Menagerie Podcast ran the Cornish Pixie Remains story, it has reemerged in the USA. Like all the great British TV comedies, the original story and images have been recycled for the American audience by a mysterious chap called James Cornan of Wilmington, North Carolina. Other than the location, the story of the Pixie skeleton discovery was copied verbatim and submitted to the 'Pictures in History' Facebook page where it was picked up by the US press. The newspapers didn't have to dig far before they realised it was initially featured on this blog back in 2016 and not only linked the page but also named me as the originator.

I'd personally like to thank James Cornan, The Charlotte Observer, The Asheboro Courier Tribune, The News & Observer, and the Pictures in History Facebook page for giving this story the exposure it deserves. Although the story was a hit in Japan and featured on prime time TV (see below), it failed to gain traction in the UK and Europe, but it appears that it has been a hit in the US. The Facebook article has been seen by 18K people, received 2K comments and been shared 25K times. Assuming a simple reach of 50 people per share, it’s been seen by 1,250,000 people. My blog page also received a staggering 17K views in one day and the Youtube video has be viewed 53K times.

The Pixie bones now reside in a secure facility in Germany where biological specimens that defy conventional science are stored. The mystery of the Pixie bones has never been solved and remains one of this century's greatest mysteries.

The attempt to prove the existence of fairies

Here's an interesting article from OZY which discusses various scientific attempts to prove the existence of fairies and similar creatures. Most of the theories are flawed from the outset and are derived from bizarre ideas such as a race of pygmies living under Stonehenge! Enjoy...

They used to be normal. Stolen away into the jungle by evil wizards who cut out their tongues, the Asiki children were transformed, their woolly hair morphing into long, sleek locks. Witchcraft destroyed their memories, and the poor, cursed children wandered the streets on dark nights in search of their long-lost homes. Or so the story went.

But Dr. Robert H. Nassau wanted to set the record straight. An elderly Christian missionary stationed in Libreville, French Congo, in 1901, Nassau, who was spiritual but not superstitious, patiently explained to townsfolk that they had nothing to fear from this mythical race of “little people.”

He had no time for such nonsense and always tried to refocus the conversation back toward his brand of Christian scientific rationalism … that is, until one particularly dark, moonless evening. With the sky covered in thick clouds, Nassau went for a walk and noticed a strange little figure following him. Upon closer inspection, he saw how the figure had strange, long black hair and struggled with a tongueless mouth to respond to his queries. A man of science, the Frenchman chased after the small being in hopes of capturing it for examination. But the only thing he caught, according to his mission log, was a single snippet of strangly, silky hair.

This account is an example of the late-19th and early-20th century’s fascination with euhemerism, the attempt to prove the existence of fairies (and other myths) through science and anthropological study. Tales like Nassau’s thrilled Victorian and Edwardian audiences, whose interest in mythical people was ignited by a growing sense of nationalism and the rediscovery of Shakespeare, particularly the Bard’s enchanting fairy-driven romance, A Midsummer’s Night Dream. Nassau’s telling reflects an effort to try and reconcile turn-of-the-century fairyphilia with the climate of scientific rationalism that characterized the Industrial Revolution.

Some 19th-century euhemerists like Alfred C. Haddon, George Laurence Gomme and John Stuart Stuart-Glennie argued that fairy tales were creative retellings of racial clashes in Bronze Age Britain. Haddon believed, for example, that fairy tales could be read “as stories told by men of the Iron Age of events which happened to men of the Bronze Age in their conflicts with men of the Neolithic age.”

The most sensational of the 19th-century euhemerist theories was presented by Scottish writer David MacRitchie in The Testimony of Tradition (1890). In this study, MacRitchie argued that fairies were actually a pygmy race of ancient Britons who once lived in the underground tombs and passageways found around archaeological sites like Stonehenge. Georg Schweinfurth’s discovery of African pygmies in the 1870s supported MacRitchie’s hypothesis, and when in the course of colonial expansion, R.G. Haliburton found a race of dwarfs living in the Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco, his theories seemed irrefutable.

Today, we know MacRitchie’s theories were wrong: “Advances in … archaeology, linguistics, anthropology and so on have since demonstrated that euhemerism might have been intellectually attractive but was not historically true,” says Adam Grydehøj, lead editor of Island Studies Journal. We now know that “a race of pygmies did not inhabit Europe prior to the arrival of a hypothesized race of Aryans.”

This approach to euhemerism combined Charles Darwin’s sensational theory of evolution with folklore, creating a scientific theory of fairies as a forgotten humanoid race. But other euhemerists, like Englishman Robert Southey, linked the fairy myth to St. Patrick’s mythical expulsion of Ireland’s snakes. The story of St. Patrick is said to be an allegorical retelling of the conversion of the Irish from paganism to Christianity in the fifth century, with the snakes representing Druidic priests who were known to have serpents tattooed on their forearms. So this branch of euhemerism claimed that the Druids, fearing persecution from their Christian

Even well into the 20th century, fairy theories evolved to reflect scientific and technological advancements. The most famous example? None other than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s attempts to explain the famous Cottingley fairy photographs through electromagnetism. Taken by cousins Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright of Yorkshire — they later admitted the photos were a hoax — these pictures depicted fairies with incandescent wings and stooped mischievous gnomes dancing and frolicking around the teenagers. “The Cottingley Fairies” consumed Conan Doyle’s imagination, prompting him to write a book in 1922 titled The Coming of the Fairies, based on his research and experiences with the girls.

Doyle theorized that fairies existed on a different vibrational spectrum, like X-rays or ultraviolet, and could be seen only by those who could “tune in to” their world. He also guessed that the reason Elsie and Frances’ fairies seemed two-dimensional was because fairies were made of pure light and cast no shadow. In reality, the fairies that baffled and enchanted a nation were nothing more than cut-out fairy-tale illustrations propped up by hat pins.

In a world rocked by dizzying techno-scientific discoveries, it seems that euhemerism and other fairy theories were a way for people in the 19th and early-20th centuries to reconnect with simpler times — ones filled with mystery and enchantment.

Disturbing Discovery of Pixie found in Falcon Nest

Could these shocking images finally be proof of the existence of pixies and fairies?

Hosts of The Mystic Menagerie, a UK based podcast were puzzled when a regular listener sent in a series of images he claims were found in a protected bird of prey next in Cornwall.

The podcast covers topics such as strange stories, folklore and the paranormal. The listener, who wishes to remain anonymous, thought that the hosts would be the ideal recipients of the images and be less likely to ridicule his disturbing discovery.

An initial private message was received via Twitter asking for an e-mail address where the images could be sent and within a few hours the strange photographs landing in the The Mystic Menagerie inbox.

The series of images show a miniature partial human skeleton. The skull, spine and ribs are present although the limbs, lower jaw and pelvis are missing. A five pence piece is also present in the images to give an indication of scale. If these are genuine then this is the smallest humanoid remains ever discovered, but how did they appear in a falcon nest?

The mysterious man who sent in the images works for a birds of prey rescue centre in Cornwall. As well as caring for sick and injured birds part of this gentleman’s job is to monitor nests of protected species for annual breeding numbers as well as preventing eggs from being stolen by collectors. During a routine check he climbed a tall tree to inspect the nest when something amongst the twigs and feathers caught his eye.

The bones were gathered up and placed in a small sample bag and taken back to the rescue centre for closer examination. Cornish folklore is rife with tales of pixies who are said to live on the high moorland areas and having grown up in the locale of Dartmoor the man could only assume that what he had found were the remains of a pixie (or piskie).

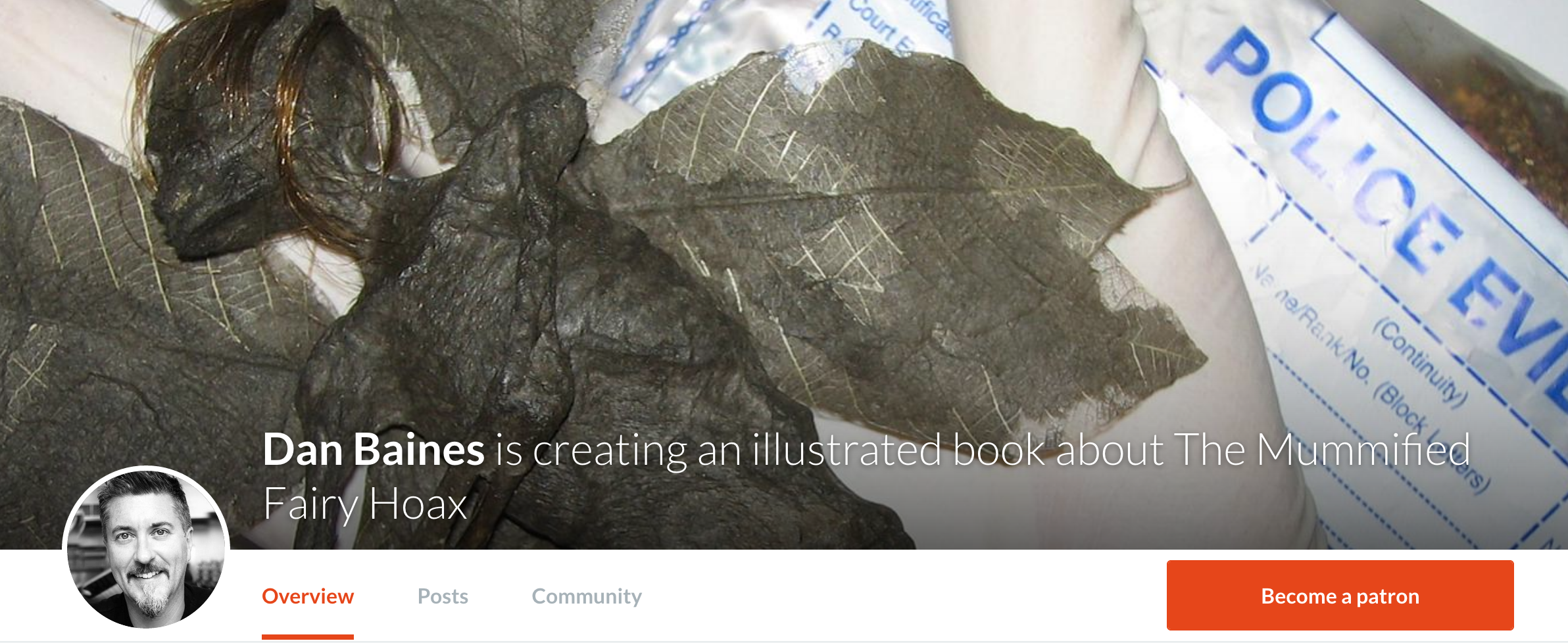

The show's host Dan Baines was responsible for the Mummified Fairy Hoax back in 2007 and is also a prop designer so he knows a fake when he sees one however, this one leaves him stumped. Co-host Freddie Valentine has been in regular contact with the owner of the images and the remains and sees no reason why he would create a hoax as he wishes to remain anonymous and will give no indication of where he works or where he found them.

Due to the colour of the skeleton it has been hypothesised that the remains are a number of years old. Falcons return to the same nest year after year so it could be assumed that a few years ago the falcon returned from a hunt with something more interesting than your standard mouse.

Dan and Freddie are currently in discussions to see if they can travel to see the remains in order to certain if they are genuine or not. In the meantime the man has agreed to record a short video of the bones to at least prove the images are not Photoshopped in any way.

This month's podcast covers this intriguing case in greater detail and more information will be posted as and when it becomes available.

Listen to the Podcast here

The Cottingley Fairies - A case study in how smart people lose control of the truth

This article by Rosa Lyster for Quartz discusses something I encountered when it was revealed that the mummified fairy images I produced were fake. Even once you unveil the truth, a significant percentage of people will choose not to believe it. My hoax had similar parallels to the Cottingley case; although I revealed the whole event to be hoax, I also publicly admitted my belief in fairies and that I had also seen them, a statement I stand by to this day.

The title of Rosa's article 'how smart people lose control of the truth' can be demonstrated even more with religion. It doesn't take fairies to show how people, even the smart ones, can believe in the most absurd things. Just look to the myths and legends purported by mainstream religion and you'll find a melting pot of unfeasible craziness where the control of the truth was lost thousands of years ago.

-

One hundred years ago, two girls went down to the stream at the bottom of a garden in Cottingley, England, and took some photographs of fairies. The fairies were paper cut-outs, which Elsie Wright, age 16, had copied from a children’s book. She and 10-year-old Frances Griffiths took turns posing with the sprites.

The girls developed the photographs in Elsie’s father’s darkroom, and presented them to their families as stunning evidence that fairies were real. Elsie’s father didn’t believe them—but her mother did. Two years later, she showed the photographs at a meeting of the Theosophical Society, a group dedicated to exploring unexplained phenomena and “forming the nucleus of a universal brotherhood of humanity.”

The story of the Cottingley fairies has always fascinated me—not because of the particulars of the case, but because of what it reveals about the life cycle of a lie. In contrast to other famous hoaxes, it doesn’t seem malicious, or even necessarily deliberate. Instead it seems to me to be a story about how a single, relatively small act of deception can lead a large group of people to lose control over the truth.

In the first photograph, Frances Griffiths stares somewhere to the right of the camera lens, pointedly not looking at the cardboard figures capering on the grass in front of her. In the second one, Elsie Wright leans forward to shake the hand of a toddler-sized boy fairy. Looking at them now, both photographs seem immediately identifiable as fakes. The figures are obviously propped-up and two dimensional. Everything, including the expressions on both girls’ faces, looks staged. It is hard to imagine the photos seeming convincing to anyone older than 12.

Yet the Theosophical Society saw things differently; the members immediately and ecstatically accepted the photographs as real. Edward Gardner, a writer and leading member of the Society, took them as proof that the “next cycle of evolution was underway” and mounted a campaign to convince the public of their authenticity. He gave lectures on the photographs, made copies of them, and passed them reverently around at meetings.

Initial press coverage was skeptical; one editorial noted that the photographs could be explained not by “a knowledge of occult phenomena but a knowledge of children.” But during and after World War I, spiritualism and mysticism gained increased influence over a grieving British public. The fairy photographs seemed to resonate with many people who were eager to believe in the existence of a better world, and in the possibility that we might be able to communicate with it.

Willingness to believe in the fairies was not a matter of intelligence or education. None other than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a trained physician and the creator of Sherlock Holmes, was dead-set on the whole notion. Doyle, a noted spiritualist, saw the photographs as evidence that communication could exists between material and spiritual worlds.

Doyle published an article about the photographs in The Strand magazine, and sent Gardner to visit the girls. Imagine being either Frances or Elsie at that moment. You have told a lie—a tale that started out as a joke, maybe, or a daydream. Now things are taking on a momentum that you cannot quite control. A stranger comes to your house with two cameras and says, No pressure, kids, but we would all just be thrilled to death if you could get us a few more shots of those fairies. Do you confess and make a fool out of everyone—or do you do what everyone clearly wants you to do, which is traipse off down to the stream and produce some more photographs?

The girls came back with three more pictures: Frances and the Leaping Fairy, Fairy Offering Posy of Harebells to Elsie, and Fairies and their Sun-Bath. These, too, look absurdly fake to modern eyes. But Gardner and Doyle fell for it again. Gardner then brought in a psychic, who claimed that the whole place was just crawling with fairies.

To me, the strangest part of this story is not that two girls pretended they knew some fairies, but rather that adults so badly wanted their encounters to be true. Not just Gardner and Doyle, whose reputations, by that point, were at least partially at stake. Lots of people were ready to believe. They twisted and massaged the narrative to add credibility. The social reformer Margaret Macmillan, for instance, emphasized that the photographers were children, and thus without motive or guile: “How wonderful that to these dear children such a wonderful gift has been vouchsafed.”

The novelist Henry de Vere Stacpool, meanwhile, insisted that the photographs were real because they just seemed truth-y: “Look at [Frances’] face. Look at [Elsie’s] face. There is an extraordinary thing called Truth which has 10 million faces and forms—it is God’s currency and the cleverest coiner or forger can’t imitate it.” The girls were telling the truth because they looked like they were telling the truth, and that was proof enough.

Eventually, people stopped caring about the fairies. Interest in the supernatural was on the wane, and Doyle was looking increasingly unhinged. The girls produced no more photographs, and the public moved on.

Every once in a while, though, someone would track down one of the girls and press them for more details, or try to get them to admit that they had been making it up. In 1983, they finally admitted that the photographs were faked, but maintained that they really had seen fairies. Elsie said that they were all faked, but Frances said that the last one was real. Frances’s daughter later insisted that fairies were real, and that her mother would never lie. You will still find corners of the internet today where people will say the same thing. Despite the girls mostly owning up to the lie, people still want to believe it, and so they will say that it is true.

The problem with telling a lie is that you often have to tell another one after that, to keep up appearances. And then it’s too late to admit what you made up, and so you just keep on lying. The issue becomes not the initial act of deception, but the fact that you’ve lied for so long—years and years and years. You may even start to believe the lie yourself. I have been thinking about it a lot lately, watching the news. Watching people on my TV lie; wondering if they even know that they are lying, as the stakes keep getting higher and higher.

The Dark Fairy Tale World of 'American Fable' First Trailer

If imitation is indeed the sincerest form of flattery, then writer-director Anne Hamilton’s “American Fable” registers as an eloquently constructed valentine to Guillermo del Toro, whose “Pan’s Labyrinth” provides her film with its haunting backbone. Gorgeously shot, and helmed with a sense of daring and verve that belies Hamilton’s greenness to feature filmmaking, this is a debut of obvious promise, although its story never quite rises to the level of its craft. Premiering in the experimental Visions program at SXSW, this tale of farmland intrigue as seen through the eyes of a dreamy 11-year-old has just as much arthouse potential as many of the supposedly more commercial entries in the narrative competition, though it may ultimately function best as a passport to bigger things for its gifted young director.

Hamilton’s introduction to filmmaking came via an internship with Terrence Malick on the set of “The Tree of Life,” and the director’s tendrils are visible from the very first shot, a dramatically swooning overhead view of a young girl chasing a chicken through monstrous expanses of corn stalks. The girl is Gitty (Peyton Kennedy, excellent), an imaginative, friendless grade schooler growing up in the farmlands of Wisconsin. The year is 1982, and overheard Ronald Reagan speeches place us right in at the beginning of the farm crisis, its gravity underscored by passing mentions of the rash of suicides in town.

Gitty adores her father, the salty Abe (Kip Pardue), who does everything he can to distract her from the fact that they’re in dire danger of losing their farm. Her factory-worker mother (Marci Miller) is pregnant with a third child, and Gitty’s older brother, Martin (Gavin MacIntosh), is a study in unhinged, unmodulated malevolence.

Wandering the farmlands on her bike, she makes a startling discovery: Locked inside her family’s unused silo is a dirty yet expensively dressed man calling himself Jonathan (Richard Schiff) who claims to have gone days without food. Though he’s short on details, Jonathan is a developer who’s been buying up farms in the area, and it doesn’t take long for Gilly to intuit that her own family has played some part in this kidnapping. As she begins bringing him food and books, the two develop a bond, with Gitty rappelling down through a small hole in the silo roof for chess lessons and reading sessions.

Meanwhile, Gitty’s father conducts some mysterious business with a Mephistophelean woman named Vera (Zuleikha Robinson), and Gitty begins to experience visions of a black-clad, horned woman striding through the countryside on horseback. These hesitant forays into the mythological realm — reaching a feverish peak with a flashy dream sequence — feel oddly underdeveloped, alternating between inscrutable and needlessly obvious, with a long montage accompanying a recitation of Yeats’ “The Second Coming” a prime example of the latter.

One of the strongest cues Hamilton takes from “Pan’s Labyrinth,” however, is the decision to allow Gitty’s own loyalties and misunderstandings to dictate the film’s p.o.v., and Kennedy ably carries the film on her back, radiating self-confidence while retaining an essential naivete and vulnerability; her many scenes of peering through doorways at conversations she doesn’t quite understand are beautifully played. Yet even accounting for this, the intrigue at the film’s center never makes total sense, and Gitty’s ultimate ethical dilemma — whether to leave Jonathan to his fate or put her own family at risk — never arrives with the right urgency. The shoehorned introduction of a few too many extraneous elements, especially a Marge Gunderson-esque retired police officer (Rusty Schwimmer), doesn’t help.

Working with d.p. Wyatt Garfield, Hamilton shoots the rural landscape with a transformative eye. These farmlands aren’t dusty expanses but rather humid, almost primordial jungles; individual frames from nighttime scenes in the family barn could easily be oil paintings of the Nativity. More than just cataloguing pretty shots, Hamilton builds an arresting aura of wonder and terror, of which Gingger Shankar’s haunting, teasing score is very much a piece.

The Dark Need for Modern Fairy Tales

This blog post by Meagan Navarro over BirthMoviesDeath.com has shed light on two modern fairy tale movies that totally slipped me by. With the unparalleled popularity of shows such as A Game of Thrones and WestWorld it's obvious that there is an increased adult need for some form of fantastical escapism. All facets of geek culture have experienced a renaissance over last few years that harken back to our childhood days. Board games, superheroes, role playing, fantasy movies; they all provide a temporary protective bubble that blocks out the modern world which is ironically dark and full of terrors.

As our world becomes a less pleasant place to live, we as adults create new ones to escape to. Either as a participant or simply a voyeur of these new universes, they provide the escapism we need to sooth the banality of the working day. We constantly look to the stars for new worlds where in fact we really need look no further than our own imaginations to experience the wonder of new discovery and adventure.

I do believe in fairies. I do. I do.

Once upon a time, fairy tales existed not for children, but for adults. They contained adult themes like rape, dismemberment, heartbreak and heroes that failed to triumph. Fairy tales were a means of historical and cultural preservation, which is what the Grimm brothers initially set out to do. At a time when the grown-ups grew bored of the fairy tale, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm sought to preserve their Germanic traditions by amassing a collection of them. Ironically, the first edition of their collection was deemed too inappropriate for children, so each successive edition continued to edit out the adult content until the final edition we’re familiar with today existed. Disney heavily borrowed from the Grimm brothers in sanitizing the fairy tales, washing away the deep historical context and oft cautionary tales in favor of happier fare. Yet, dark times call for dark art, and a resurgence of fairy tale films geared toward adults might be the reminder of the past that we need to get us through our future.

Director Agnieszka Smoczynska’s stunning feature debut, The Lure, relies heavily on Hans Christian Andersen’s version of The Little Mermaid but is imbued with Poland’s cultural climate during the 1980s under Communist Russian rule. That the narrative is centered around this particular fairy tale is no small coincidence considering the significance of mermaid lore to Warsaw. Mermaid sisters Golden and Silver’s longing to see the pristine shores of America serves as a metaphor for immigration, but their journey also rings true on an emotional level when it comes to the highs and lows of first love. The nuanced layers of Robert Bolesto’s screenplay are rendered even more complex by the defiance to stick to any one genre. The result is a richly compelling Siren’s song of carnal lust, blood, and singing mermaids in a cabaret act set against a real setting of nightclubs and sadness.

Quietly released last year was Italian filmmaker Matteo Garrone’s adaptation of fairy tales by seventeenth-century poet Giambattista Basile. Well, more like a partial adaptation; his book has 50 stories and Garrone adapted only three of them in Tale of Tales. With much of Basile’s work overshadowed by Grimm’s adaptation, Garrone took the tales back to their medieval beginnings, honoring the Neapolitan history behind the stories. Whereas The Lure took on a more modern aesthetic, Tale of Tales retains a 17th century vibe. Despite appearances, though, Garrone’s film connects with modern audiences because the problems faced by the film’s characters are still just as relevant today as they were centuries ago. You know, except for the giant flea, cave monsters, or unwitting sea creature, but still. The three female-centered tales featured in Garrone’s film still apply to the modern woman - feelings of inadequacy or jealousy in both love and lust, the yearning for motherhood and the inability to let go, and the brutal sting of exposure to the outside world during the transition from childhood into adulthood. Not only did Garrone realize fairy tales are effective because they play off of common archetypes, but the real magic lies within the actual telling of the tale.

On the other end of the live-action fairy tale retellings lies Disney, an empire known for animated fairy tales far removed from their origins in favor of saccharine wish fulfillment. Good always triumphs over evil, and the princesses always get their happily-ever-after, nearly always in the form of a prince. For all of Disney’s messages about being unafraid to reach for your dreams, they seem afraid to detour from the blueprints of their animated classics when it comes to their live-action retellings. 2015’s Cinderella brought us a sweet yet by-the-numbers rehash of the 1950 animated version. As did 2016’s The Jungle Book, despite the talented cast behind it. While I have no doubt that audiences will flock to the theater in March for Beauty and the Beast, I can’t help but notice that it too mirrors its animated counterpart in every way. Disney takes more risks with their original properties, like Enchanted, but they still pay heavy homage to the classics. Disney’s fear of change isn’t baseless, though. Their intent to attract an older audience works against them, as those clinging to nostalgia likely won’t want their favorite tales altered. This is precisely the reason why we need that change.

The world is a dark place right now, and it seems to grow just a bit dimmer each day. Fairy tales bring harsh truths and cautionary tales in a digestible format while still reminding us that the world is bigger than we could ever know. They remind us that while things may seem dire, there’s still hope. Even more than that, fairy tales remind us of our heritage and bridge cultural divides. We need fairy tales like The Lure or Tale of Tales. These dark, violent, and horrific stories can allow for reflection of the past and potential course correction for the future. They can bring new truths and traditions with each subsequent telling, if we allow that growth. In a time where listening is sparse and voices are loud, the world needs more killer mermaid musicals.

Jordskott Season 2 Trailer Released

One of my TV highlights of last year is back this autumn with more eerie fairy folklore driven drama. This article from The Killing Times dissects the new 2 minute preview to see what we might expect from Henrik Björn's mystical masterpiece.

Although Swedish series Jordskott was broadcast here in the UK on ITV Encore, it did fantastically well internationally, and was sold and played out in 50 countries. It was an insane, bonkers series that told the story of Detective Inspector Eva Thörnblad (Moa Gammel), who returns to Silver Height seven years after her daughter Josefine disappeared by a lake in the woods. The body was never found and the girl was believed to have drowned. Then a boy vanished without a trace and Eva was intent on finding out if there was a link to her daughter’s disappearance. That was just the start of things: add in some ancestral weirdness with her dad, timber empire man Johan Thörnblad, witches, woodland folk and strange black liquid and Jordskott was like your traditional Scandi Noir mixed with a fairytale. Finally we have confirmation of a second series and a trailer to go with it.

Let’s check in with creator, Henrik Björn:

The teaser begins with an exclusive and complete small scene in a way that overlaps season one and two. This scene happens right now in Silver Height. It’s Jörgen Olsson, the surviving brother Olsson, who will find a car in the woods. Harry Storms car. Storm was the man who caused so much [trouble] in Silver Height in pursuit of who kidnapped the children. In the car there was the whole of Storm’s investigation and Jorgen realises that Storm has gathered information on Esmeralda (Happy Jankell). She is the same girl who Jorgen accused of killing his brother Eddie. It felt great to give the fans a little taste of jordskott-candy for Christmas.

You can see the trailer below, but what’s interesting is that the city is being framed as a major location in this second series, rather than the pretty much exclusive woodland setting of series one.

It is partly familiar and partly new. There are some places that we like to see again. At the same time, I did not stand still in season one, we’re going forward. It happens new things that need to be managed. Events of season one obviously affects the runner-up, but the new stands on its own and it is necessary.

There’s also a shot of the witch, Ylva, who seemingly died in series one. Intriguing. Anyway, filming begins in January (well, at least continues) and carries on until the summer, and Björn says that the action will pick up two years after all the drama of series one. What’s more, my favourite character – police chief Göran Wass (the brilliant Göran Ragnerstam, who was also in the equally bonkers Ängelby this year, returns).

The big question is: will we see Muns and find out who he is (I realise that to non-Jordskott watchers, this will make no sense whatsoever). More news as I get it…

If you're a Jordskott fan you may also be interested in my latest book project 'Fairy Rings & Monstrous Things' which is currently being supported via kindred spirits on Patreon.

The Mummified Fairy Hoax is being turned into a book and you can be part of it!

The time has finally come to for me to start writing my account of the mummified fairy hoax. 2017 will be 10th anniversary of the event that changed my life in ways I could have never imagined. The folly of the mummified fairy may have destroyed my professional career but the opportunities and adventures that ensued have ironically turned the curse into a gift of new life and discovery.

The project will be hosted through Patreon, which for those who are unaware, is a way for creators to fund their work through subscription payments from their fans. As I am primarily a prop artist I can offer more rewards to my supporters than just written work. I plan to illustrate my own work and create limited edition fairy sculptures for the top level subscribers. It’s a great opportunity for you to get a piece of my work at a fraction of the cost AND get all of the written material & additional art as a bonus.

The story goes far beyond everything I have ever revealed in my lectures. I give a hint at the end of my presentation about a mysterious letter received from one of the UK's highest security mental institutions, but the story is far from over. There's Nazi cults, secret tunnels, derelict WWII military installations, arcane secrets and close encounters with the security services.

How does all of this relate to the original mummified fairy hoax? Well, you'll have to become a patron to find out.

In a creative kick start to 2017 the project launched today so if you’d like to join me on my unexpected journey and pledge your support it will be an honour to have you aboard.

You can find out more information and support the project here.

Pan’s Labyrinth: A Decade of Fairy Tales & Fascism

It's 10 years since the release of Guillermo del Toro's compelling and deeply involving masterpiece. This terrifying and visually wondrous fairy tale for adults blends fantasy and dark drama into one of the most magical films that is still as refreshingly different today as it was back in 2006.

A celebrate this cinematic classic I share here with you a great article by Gary Shannon from TheYoungFolks.com and for you movie geeks, 15 things you may or may not know about Pan's Labyrinth.

Pan’s Labyrinth opens with a shot moving in a reverse: It’s night and a young girl lies on the floor as blood streaming from her nose begins to shrink back in. It’s striking, haunting, horrifying and tragic, when you see it for the first time you’re not completely sure what to make of it, or at least not yet. The young girl is Ofelia and director Guillermo del Toro indicates something crucial about her character. Ofelia is dying, but just as the light in her eyes begin to fade the camera zooms into their overwhelming blackness. From there we see, at a distance, a similar girl running through a vast array of ancient cloisters and spires. A narrator describes the scene but the image alone tells us all: A princess is trying to escape her kingdom of darkness, and as she ascends a spiral staircase her world becomes brighter. As she reaches the top of the staircase a bright flash overpowers her and, as the narrator describes, the princess is consumed by the sunlight and becomes a mortal.

In the next shot we see Spain in 1944. Pan’s Labyrinth takes place after the Spanish Civil War, just as dictator Francisco Franco ascends to power and, for over the next 30 years, becomes one of the country’s most maligned rulers. In a considerably less abstruse establishing shot we see a caravan of well heeled cars (for rich people), inside one of them is Ofelia, an inspirited young girl, and her pregnant mother. The two are traveling to meet Ofelia’s stepfather, Captain Vidal, the despotic head of a backwoods military compound. There he reigns over the area’s inhabitants with a rigid (and evil) authority indicating that he’s the compound’s veritable dictator. Guillermo del Toro’s world is oppressive, scary and real. So where does the fantasy come into play?

Ofelia is a bookworm who relishes in her space and freedom. So much so that when all the cars stop (to relieve her mother of a debilitating morning sickness) Ofelia veers from the caravan’s path. Deep in the woods she encounters a strange insect which, in fact, happens to be a fairy. One night the fairy visits Ofelia and, urging her to come with it, she follows it to a stone labyrinth hidden in the wooded outskirts of the compound. There she meets a weird being dubbed the Faun, he’s made of earthy skin, boasts a dubious affability and wears an off-putting, cat-like smile. The Faun’s words are elongated and grandiose, he lures Ofelia with the promise of riches of eternity inside a fairytale kingdom, and refers to her as its long lost princess who had run away from the kingdom. Ofelia, an idealist, accepts the Faun’s terms. To obtain her immortality Ofelia must complete 3 separate tasks, each one strange and terrifying. Guillermo del Toro’s world is magical, mysterious and make-believe. So where does the realism come into play?

Pan’s Labyrinth is a film of two vastly contrasting textual layouts. Since its release they’ve spawned several theories and perspectives of what the binary concept of fantasy & reality in the film actually means. A more pessimistic perspective assigns Pan’s Labyrinth two worlds as a eulogy on the power of escapism, how Ofelia’s entrenched journey through mystical realms are products of childish delusions created to help the girl come to grips with a harsher reality. Guillermo del Toro, however, despite encouraging people to make-up their own assumptions of the film, believes that the fairy tale kingdom in Pan’s Labyrinth was real. Which means it has to be, right? Since its release 10 years ago ideas have swelled into even more convoluted arguments, all of which are theoretical and, unfortunately irrelevant. Films, like Pan’s Labyrinth, can show us reality and fantasy, but neither description consigns the film to be either real or fake. As the fantasy novelist Lloyd Alexander is quoted to have said, “Fantasy is hardly an escape from reality. It’s a way of understanding it.”

Reading a good book, as Ofelia does, doesn’t offer any sort of escape from her stepfather’s reign of terror but broadens her mind to life’s endless possibilities, outside of consigned oppression, militaristic fascism and psychological totalitarianism. There is a character in Pan’s Labyrinth, Doctor Ferreiro, a physician and a pacifist, who secretly sympathizes with the rebels fighting Captain Vidal. He questions the Captain, something the Captain hates, and at times the Doctor even undermines him. The Doctor’s deciding moment comes in the form of an insult, aimed toward the Captain, which in essence reflects the film in its entirety: “But Captain, to obey, just like that, for obedience’s sake . . . without questioning . . . that’s something only people like you do.” Ofelia’s mother, on the other hand, acts as an antithesis to everything the Doctor stands for, the woman is confined to the security of her abusive husband’s autocracy. In a heartbreaking sequence the woman literally casting her life (manifesting as a mandrake root) into the fireplace and says to Ofelia, in a tragic rejection of life itself, “Magic does not exist. Not for you, me or anyone else.”

Then we have characters like Mercedes and Ofelia, two people who seem to exist on the polarizing center of obedient confinement and rebellious liberation. Both Mercedes and Ofelia seem to be the respective protagonists of their own stories. Mercedes is an insider for the rebel battalion her brother commands. She acts as a maid, working undercover to learn of Captain Vidal’s battle strategies, as well as smuggling things out of the compound to supply his men with food, medicine and other kinds of sustenance. Ofelia, on the other hand, seems cut-off from the conflict despite being very much in the midst of it. Her mind, instead, seems intent on completing her 3 tasks where she must remain unquestioningly obedient to the Faun’s stringent terms. We know where their hearts lie, Guillermo del Toro likes these characters, but their choices and actions are fraught with complex moral dilemmas. Not even the fairy tale aspect of Pan’s Labyrinth comes with easy answers . . .

In Pan’s Labyrinth’s climax we see Ofelia with her infant brother running toward the labyrinth. It’s in the midst of a decisive battle where the rebels begin outnumber the compound’s soldiers. Captain Vidal is hot on her trail, carrying in his hand a pistol. As Ofelia arrives to the labyrinth’s center the Faun is there to greet her. This time though he feels oddly unwelcoming, carrying the knife she obtained during her second task. The Faun presents her with a third task: To procure a small drop of blood from her brother. Ofelia backs away, hesitant to listen to the Faun, and outright refuses to harm her brother. By this point Vidal arrives, and much like the Faun, he too wants Ofelia’s brother. Vidal can’t see the Faun but sees Ofelia and her brother clearly. He delicately takes the brother from Ofelia’s arms and, with striking visual reserve, he shoots the girl.

Pan’s Labyrinth ends the same way it begins, but this time it’s not in reverse: It’s night and a young girl lies on the floor as blood streaming out of her nose. This time we know who she is. This time the moment, instead of being played for mystery, is played for a devastatingly tragic grandeur. Dying, Ofelia sees the kingdom she was promised. Is it a delusion? Did she pass the Faun’s test? We don’t completely know but it’s happy and resolute. Ofelia is congratulated by the Faun, but for what? She refused to complete the third task. Well, not exactly. The Faun reveals that by refusing to take the blood of the innocent and, ultimately, for thinking for herself she had won her reward. It’s almost too happy of an ending. The shot dissolves back to the dying Ofelia. What is del Toro saying about Ofelia, or the Spanish Civil War, or about people in general? In a satisfying closing note, Captain Vidal surrenders the son and dies at the hands of Mercedes and the remaining rebel battalion, but not before Mercedes shows one last act of defiance:

Vidal: “Tell my son the time that his father died. Tell him—”

Mercedes: “No. He won’t even know your name.”

In the world of fairies, fauns and eternity, Ofelia’s goodness earned her a happily ever after. In the world of dictators, wars and tragedies Ofelia’s goodness earned her a sad, lonely death. Whether Ofelia’s dying visions were illusory or real we can’t deny del Toro’s simple truths. Happy endings don’t exist in the real world, the good are punished and the wicked are rewarded. And like those who sought to liberate their country in the Spanish civil war Ofelia’s self-determinism came at the cost of her life. As she lays dying, Mercedes grieves over her lifeless body. A strange image follows, Ofelia smiles. Why? Because like the runaway princess in the opening Ofelia is too finally escaping her kingdom of darkness.

14 Fantastical Facts About 'Pan's Labyrinth'

Between his modest comic book hits Hellboy and Hellboy II: The Golden Army, imaginative Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro made a film that was darker and more in Spanish: Pan's Labyrinth, a horror-tinged fairy tale set in 1944 Spain, under fascist rule. Like many of del Toro's films, it's a political allegory as well as a gothic fantasy. The heady mix of whimsy and violence wasn't everyone's cup of tea, but it won enough fans to make $83.25 million worldwide and receive six Oscar nominations (it won three). On the tenth anniversary of the film's release, here are some details to help you separate fantasy from reality the next time you take a walk in El Laberinto del Fauno.

1. IT'S A COMPANION PIECE TO THE DEVIL'S BACKBONE

Del Toro intended Pan's Labyrinth to be a thematic complement to The Devil's Backbone, his 2001 film set in Spain in 1939. The movies have a lot of similarities in their structure and setup, but del Toro says on the Pan's Labyrinth DVD commentary that the events of September 11, 2001—which occurred five months after The Devil's Backbone opened in Spain, and two months before it opened in the U.S.—changed his perspective. "The world changed," del Toro said. "Everything I had to say about brutality and innocence changed."

2. IT HAS A CHARLES DICKENS REFERENCE

When Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) arrives at Captain Vidal's house, goes to shake his hand, and is gruffly told, "It's the other hand," that's a near-quotation from Charles Dickens' David Copperfield, when the young lad of the title meets his mother's soon-to-be-husband. Davey's stepfather turns out to be a cruel man, too, just like Captain Vidal (Sergi López).

3. DUE TO A DROUGHT, THERE ARE VERY FEW ACTUAL FLAMES OR SPARKS IN THE MOVIE

The region of Segovia, Spain was experiencing its worst drought in 30 years when del Toro filmed his movie there, so his team had to get creative. For the shootout in the forest about 70 minutes into the movie, they put fake moss on everything to hide the brownness, and didn't use squibs (explosive blood packs) or gunfire because of the increased fire risk. In fact del Toro said that, except for the exploding truck in another scene, the film uses almost no real flames, sparks, or fires. Those elements were added digitally in post-production.4. IT CEMENTED DEL TORO'S HATRED OF HORSES.

The director is fond of all manner of strange, terrifying monsters, but real live horses? He hates 'em. "They are absolutely nasty motherf*ckers," he says on the DVD commentary. His antipathy toward our equine friends predated Pan's Labyrinth, but the particular horses he worked with here—ill-tempered and difficult, apparently—intensified those feelings. "I never liked horses," he says, "but after this, I hate them."

5. THE FAUN'S IMAGE IS INCORPORATED INTO THE ARCHITECTURE

If you look closely at the banister in the Captain's mansion, you'll see the Faun's head in the design. It's a subtle reinforcement of the idea that the fantasy world is bleeding into the real one.

6. IT MADE STEPHEN KING SQUIRM

Del Toro reports that he had the pleasure of sitting next to the esteemed horror novelist at a screening in New England, and that King squirmed mightily during the Pale Man scene. "It was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life," del Toro said.

7. IT REFLECTS DEL TORO'S NEGATIVE FEELINGS TOWARD THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

Del Toro told an interviewer that he was appalled by the Catholic church's complicity with fascism during the Spanish Civil War. He said the priest's comment at the banquet table, regarding the dead rebels—"God has already saved their souls; what happens to their bodies, well, it hardly matters to him"—was taken from a real speech that a priest used to give to rebel prisoners in the fascist camps. Furthermore, "the Pale Man represents the church for me," Del Toro said. "He represents fascism and the church eating the children when they have a perversely abundant banquet in front of them."

8. THERE'S A CORRECT ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF WHETHER IT'S REAL OR ALL IN OFELIA'S HEAD

Del Toro has reiterated many times that while a story can mean different things to different people, "objectively, the way I structured it, there are clues that tell you ... that it's real." Specifically: the flower blooming on the dead tree at the end; the chalk ending up on Vidal's desk (as there's no way it could have gotten there); and Ofelia's escape through a dead end of the labyrinth.

9. THE PLOT WAS ORIGINALLY EVEN DARKER

In del Toro's first conception of the story, it was about a married pregnant woman who meets the Faun in the labyrinth, falls in love with him, and lets him sacrifice her baby on faith that she, the baby, and the Faun will all be together in the afterlife and the labyrinth will thrive again. "It was a shocking tale," Del Toro said.

10. THE SHAPES AND COLORS ARE THEMATICALLY RELEVANT

Del Toro points out in the DVD commentary that scenes with Ofelia tend to have circles and curves and use warm colors, while scenes with Vidal and the war have more straight lines and use cold colors. Over the course of the film, the two opposites gradually intrude on one another.

11. THAT VICIOUS BOTTLE ATTACK COMES FROM AN INCIDENT IN DEL TORO'S LIFE

Del Toro and a friend were once in a fight during which his friend was beaten in the face with a bottle, and the detail that stuck in the director's memory was that the bottle didn't break. That scene is also based on a real occurrence in Spain, when a fascist smashed a citizen's face with the butt of a pistol and took his groceries, all because the man didn't take off his hat.

12. DOUG JONES LEARNED SPANISH TO PLAY THE FAUN

The Indiana-born actor, best known for working under heavy prosthetics and makeup, had worked with del Toro on Hellboy and Mimic and was the director's first choice to play the Faun and the Pale Man. The only problem: Jones didn't speak Spanish. Del Toro said they could dub his voice, but Jones wanted to give a full performance. Then del Toro said he could learn his Spanish lines phonetically, but Jones thought that would be harder to memorize than the actual words. Fortunately, he had five hours in the makeup chair every day, giving him plenty of time to practice. And then? Turns out it still wasn't good enough. Del Toro replaced Jones's voice with that of a Spanish theater actor, who was able to make his delivery match Jones's facial expressions and lip movements.

13. NEVER MIND THE (ENGLISH) TITLE, THAT ISN'T PAN